Već nekoliko godina unazad pratim izuzetno kvalitetan blog o lavkraftovskim temama pod nazivom DEEP CUTS IN LOVECRAFTIAN VEIN.

I kao što je pun internet nekakvih bezveznjačkih besposlenih blogera koji piskaraju koješta, ali samo jedan blog piše Doktor za Horor, vaš voljeni Ghoul, tako je isto prepun internet bezveznjaka koji kenjaju koješta o Lavkraftu, ali samo jedan blog među njima piše jedan od vrhunskih posvećenika i poznavalaca, te autor izvanredne knjige SEX AND THE CTHULHU MYTHOS (moje najvrelije preporuke! smesta nabavite i proučavajte!) – Bobi Deri (Bobby Derie).

Krajem prošle godine gospodin Deri me je kontaktirao i ponudio mi opciju da u okviru planirane serije tekstova, u kojima bi niz spoljnih saradnika Lavkrafta sagledavao iz nekih opskurnijih, skrajnutih perspektiva, i ja ponudim svoj, srpski ugao, u kojem ću se pored ostalog osvrnuti i na Lavkraftov poznati zazor prema slovenskim rasama…

|

| Druga Lavkraftova knjiga na srpskom, proleće 1990 |

Taj tekst je bio pristojno honorisan (jebote, 12 godina pišem za The Cult of Ghoul i nikad dinara ne videh od toga, a sad, prvi tekst za Deep Cuts in Lovecraftian Vein i odma – devize, devize!) što je bio dodatni čokoladni preliv na ionako dobru tortu, tako da sam s velikim zadovoljstvom sročio tekst u kojem pišem, otprilike, o tri glavne stvari: 1) o odocnelom dolasku Lavkrafta među Srbe i o tome šta mi je u ranoj mladosti značio; 2) o Lavkraftovom uticaju na moje prozno pisanje i druge stručne aktivnosti, i 3) o tome kako sam, kao Srbin, primio Lavkraftovu antipatiju prema Slovenima kao inferiornoj rasi.

Pa, sada je taj moj tekst napokon objavljen na pomenutom blogu i nalazi se OVDE.

|

| Jedino izdanje Lavkrafta na srpskom, na ćirilici |

Ponavljam i naglašavam: ne idite tamo samo zbog mog teksta, ima tamo bezbroj drugih, odličnijih, vrednijih, ređih saznanja i uglova za svakog pravog posvećenika u HPL kult! Idite, čitajte, uživajte, obožavajte!

A s dopuštenjem g. Derija, moj tekst možete čitati i sada i ovde. Pa, evo ga. Pročitajte pa recite ponešto na ove teme iz svog ugla: kad i kako i gde ste prvi put otkrili Lavkrafta? Kako i zašto vam je delovao? Koliko vam smetaju njegovi rasistički nazori? Slutim da mnogim Srbljima njegova nesklonost crncima uopšte ne smeta, ali mnogi među vama su tek sad primetili da on ni Slovene nije voleo… Odnosno, primetiće to u donjem tekstu… Pa, pročitajte, a onda – recite!

“A Serbian Look At Lovecraft”

© by Dejan Ognjanović

originally published at

Deep Cuts in a

Lovecraftian Vein

https://deepcuts.blog/2022/06/04/a-serbian-looks-at-lovecraft/

I was born into a culture in which Lovecraft was not a household name: hell, he was not even a cult name. He came to my neck of Balkan woods pretty late. And yet, eventually he ended up as the subject of my first, unfinished MA thesis, and one of the subjects of my (completed and defended) PhD thesis, and ultimately an author whom I translated and edited in his later appearances in Serbia. He is also a spirit looming above and behind many of my horror fiction writings, despite the fact that they are not set in New England but in Old Serbia.

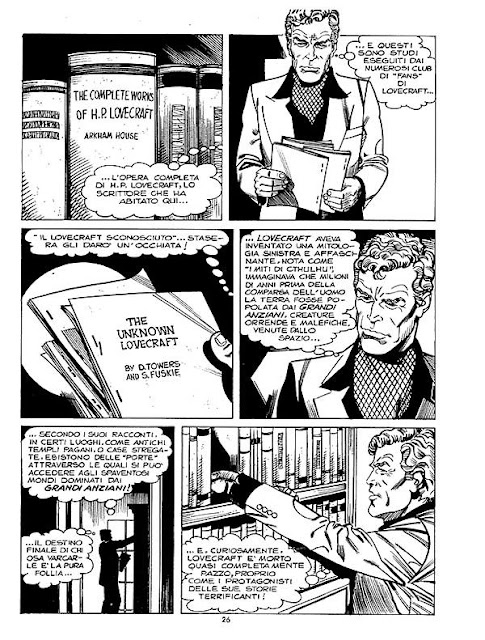

In my childhood, in the early 1980s, during my initial investigations into the scarce horror fiction then available in Serbian, Lovecraft was literally unknown. Not a single story by him had been translated by my late teens, i.e. by 1989. Thus my first encounter with him was indirect – it was through the idea of Lovecraft, as re-imagined in an Italian comic series Martin Mystere, the episode “The House at the Edge of the World” (“La Casa ai confini di mundo”, 1982), which I read in the summer of 1986, when I was 13.

It was a love at first sight: for the first time I encountered the concept of houses haunted not by ghosts or any traditional monster, but by unnamable inter-dimensional entities; it also involved places serving as portals into non-Euclidean spaces, nameless cosmic vistas, alien temples and weird-looking gods/demons. Even from a distance of 35 years, I can safely claim that this episode is one of the most inspired, sinister and clever comic adaptations of HPL’s writings, based more on his spirit than on any particular tales. Up to that point I had not been aware that one was allowed to mix real places and people (Lovecraft himself included) with the fictional ones. I was instantly enthralled by it, and it has remained my favorite approach in my own fiction.

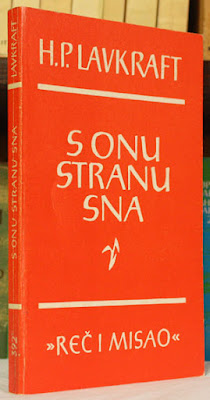

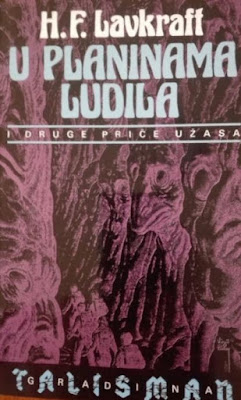

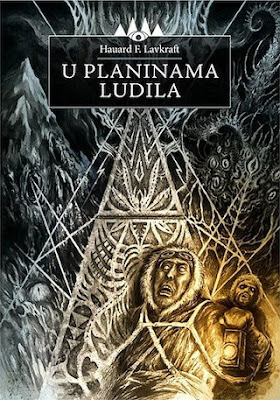

Strangely enough, for more than half a century since Lovecraft’s death, none of his fiction had been available in Serbian, and then, out of nowhere, came a sudden boom in 1990-1991. Within twelve months three books were published: a slim and pretty random selection of mostly minor stories

|

| Prvo izdanje Lavkrafta na srpskom, decembar 1989 |

was followed by his two major novels, At the Mountains of Madness and The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, the latter accompanied by his essay on Supernatural literature which, at the time, served as a more than welcome guide to authors and works then locally mostly untranslated. While Lovecraft was elsewhere, at the time, mostly relegated to the provenance of small presses and independent publishers, in Serbia all initial three books were published by major, state-owned publishers (Rad and Bigz), or at least state-and-local municipality-funded (Gradina).

The sudden boom of Lovecraft in this region was immediately followed by the explosions of Yugoslavia’s break-up in bloody civil wars. A coincidence? One is left to wonder… Later, when I started writing my own horror fiction, I used HPL’s large-scale entrance into Yugoslavia through Serbia just before the war as a springboard for a mixture of fact and fiction in a story titled “Necronomicon, The Third, Updated Edition” (“Nekronomikon: treće, dopunjeno izdanje”, 2014), where Nyarlathotep, the crawling chaos, comes to the environment ripe for destruction and quickly joins forces with the local politicians.

|

| Prvi niški Lavkraft: Gradina, jesen 1991 |

My earlier story “Dagon, God of the Serbs” (“Dagon, bog Srba”, 2010) was a playful parable about a country in transition from one type of totalitarianism to an apparent “democracy” which, you guessed it, hides the cosmic evil in plain sight, and where “the new normalcy” of strange cults and weird worship is quickly taken for granted. Black-robed Orthodox priests are easily supplanted by the black-robed cultists who take over the Byzantine churches for human sacrifices and other rituals. The story’s title and central conceit is rooted in an actual medieval document which mentions that Serbs used to worship a god named Dagon.

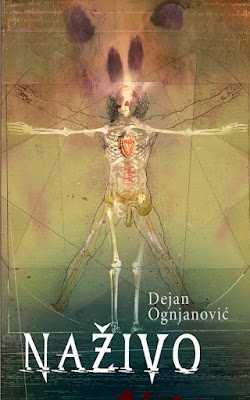

My most ambitious deployment of Lovecraft was in my first novel, In Vivo (Naživo, 2003). I have never been a fan of HPL pastiches or “mythos fiction” written by his epigones, nor did I intend to become one myself. Therefore, in the plot dealing with the occult background of the civil wars and various brutalities in Balkan’s mid-1990s, Lovecraft is explicitly referred to only twice: in a cruel ritual invocation Yog-Sothoth is mentioned as just one of the many names for the Guardian of the Gate, equal to Choronzon (also named); and on the suggestive inscription on a mysterious man’s T-shirt, which after much divining of the hyper-stylized script, says: Nyarlathotep. What I strove for in that novel, rather than puerile “winks” and homage, was to apply Lovecraft’s notions of what constituted good storytelling, with painstaking realism in all aspects except the (suggestions of the) fantastic, with carefully placed hints alluding towards the bigger picture which is never explicitly delineated. Always having in mind Lovecraft’s ideals, I also strove to build a strong atmosphere of doom and gloom, for which Serbia in the 1990s, under sanctions, and affected by inflation, neighboring wars and various forms of degradation, was all too perfect a background.

|

| Prva primena Lavkraftovskog horora u srpskoj prozi |

As can be divined from the above, Lovecraft’s fiction for me has never been just a repository of cool monsters, demons and other paraphernalia: when I used them literally, it was in a tongue-in-cheek, openly satirical manner, but I mostly avoided them, or used them sparingly, when I was trying to say something more ambitious. It is sad, but true, that when I finally came across all of his writings in the mid-1990s, I found his pessimistic vision about humanity and the universe to correspond with what I’d already seen and felt in my own environment, but also, indirectly, in the rest of the world.

|

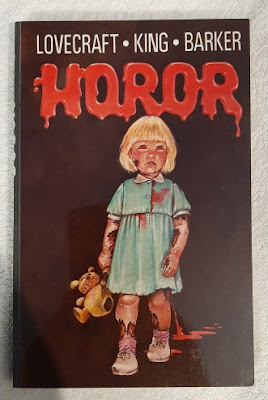

| Jedno od prvih ukazanija HPL-a na srpskom: 4 priče u omnibusu, proleće 1990. |

Yes, it took a full decade between my first encounter of the idea of Lovecraft, in a comic, and actually finding and reading all of his masterpieces, including “The Call of Cthulhu” and “The Shadow over Innsmouth”, because it was pretty difficult or next to impossible buying books in English in Serbia during economic sanctions in the 1990s. However, when a friend brought me a few Lovecraft’s collections from London, my mind was blown. These stories were all that I was imagining and hoping for during those ten years, and then some! This aspect may be hard to imagine for a today’s reader who is one click away from ordering anything by HPL through on-line sellers, or from accessing it online, across the web. But, in the age before the internet and before books in English became reasonably accessible, for Serbian readers Lovecraft was at least twice as esoteric. And yet, I must stress that in my case Lovecraft’s long unavailability was instrumental in whetting my horror appetites and my imagination: before I was able to read his best works, I imagined them, I thought about them and I dreamed them.

|

| Prvi znalački, stručni izbor Lavkraftovih priča na srpskom |

I was aware of Lovecraft’s denigrating attitude to immigrants, including Slavs, especially Poles, among other races and nations turned monstrous in “The Horror at Red Hook”. I also came across his early story, “The Street” (1920), in which an old Yankee narrator feels a particular repugnance caused by the appearance of a Slavic business venture, “Petrovitch’s Bakery”, in his beloved, ethnically pure WASP town and street. “Of the various odd assemblages in The Street, the law said much but could prove little. With great diligence did men of hidden badges linger and listen about such places as Petrovitch’s Bakery, the squalid Rifkin School of Modern Economics, the Circle Social Club, and the Liberty Café. There congregated sinister men in great numbers, yet always was their speech guarded or in a foreign tongue.” Petrovitch is a common Russian family name, but it is also found often among Serbian surnames.

|

| Prvi Orfelinov Lavkraft |

This story, admittedly minor, exemplifies the author’s prejudice towards Slavic races, including Serbs, which can be found expressed more explicitly in his essays and letters. For example, talking about “greater Serbia (Jugo-Slavia)“ in a letter to Arthur Harris he describes it as „a relatively unknown Eastern race“ (13 Dec 1918, Letters to Rheinhart Kleiner and Others, p. 237). His ignorance of the region, and the race, are typical of his times, because Serbia, until the outbreak of World War I, was perceived, if at all, as just another insignificant „land behind the great forest“. At least he was willing to admit as much: “I’d hate to admit how little I know about the Slavonic nations, the Tartars, and even of Germany. [...] The Balkans certainly are a hopeless mess, with wide racial variations“ (H. P. Lovecraft to Robert E. Howard, 16 Aug 1932, A Means to Freedom, vol. 1, p. 367). A good example that Lovecraft was far from alone in such estimate, and with similar arguments, is found in Howard’s letter from 9 Aug. which actually instigated the above statement, where he says: “But what a tangled mess and confusion Balkan history is! And what a mixture of blood-strains the average Balkan must be! Celtic, Roman, German, Slav, Greek, Mongol, Turkish – no wonder they’re always ham-stringing each other” (A Means to Freedom, vol. 1, p. 345).

|

| Novi, moj prevod jednog od najboljih horor romana svih vremena |

A “hopeless mess“ is a phrase which could just as easily be used to describe Lovecraft’s anti-Slavic rant in his letter to the Gallomo, of 6 Oct 1921, in which he claims: “(I) do not think any Slav nation will rise even to semi-civilisation. Whatever the Slav conquers will be lost to civilisation, for the race-stock is deficient. Slavs are emotional and irrational…“ (Letters to Alfred Galpin, p. 112). Still, I did not mind the implications of his private rants nor his published, fictional diatribes, for several reasons. First, I do not self-identify as a Serb so fully and unreservedly that I would take such minor offences, clearly based on Lovecraft’s meager acquaintance with this subject (and on unfortunate race theories about Germanic and Anglo-Saxon supremacy, widespread in his times) as obstacles for my reading enjoyment,even in such a poor and shallow parable as “The Street”. Second, most of my favorite authors held some questionable views or had lifestyle choices which I may not fully condone (M. De Sade, E. A. Poe, L. F. Celine, W. Burroughs, T. Bernhard), yet it never occurred me to “cancel” them or stop reading their fictions because of certain aspects of their thoughts or deeds which I did not share. Third, from reading HPL’s letters I realized the expanse of his mind, which included willingness to amend his ideas based on new findings, and felt certain that, if only he’d had a chance to meet some great Serbs who lived and worked in USA at the time, like Nikola Tesla or Mihajlo Pupin, he’d be more respectful, and perhaps even eager to enjoy some pita, or burek, from “Petrovitch’s Bakery”.

|

| Burek (sa sirom, naravno) |

With only slightly bigger exposure to those “aliens”, he wouldn’t have perceived them as “sinister men” nor would he have feared their speech as “guarded” and “foreign”. After all, Tesla with his mysterious personality and public exhibitions of the new electric power may have at least partially inspired his conception of Nyarlathotep as a sinister “itinerant showman” with nightmarish exhibitions and performances… This connection, first suggested by Will Murray in his essay “Behind the Mask of Nyarlathotep”, is found by S. T. Joshi to be likely (see his “Explanatory notes” in H. P. Lovecraft, The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories, Penguin, 2002, p. 369). Had Lovecraft actually met Tesla, say, during his stay in New York, he might have even befriended the eccentric, reclusive and world-weary Serbian genius whose attitudes towards humanity, wealth and sex, among others, were rather similar to his own. Perhaps based on such an acquaintance a more benevolent character would have been created: someone closer to his good professors and scientists than to avatars of the Old Ones.

In any case, when in 2008 the opportunity arose for me to edit the first ambitious selection of Lovecraft’s best horror tales in Serbian, in a large format 600-pages hardcover with original illustrations, titled Nekronomikon, I accompanied the tales with my introduction, a lengthy afterword, annotated bibliography, detailed author’s biography and chronology of his entire opus, so that Serbian readers could, for the first time, see the full scope of his poetics and the literary context which shaped it. This was continued in a series of books (twenty five so far), named “Poetics of Horror”, for which I edited two more selections of Lovecraft’s stories, plus I did a new translation of Mountains, and among the authors I presented, most of them for the first time in Serbian, were many of his major influences (Machen, M. R. James, Blackwood, Hodgson) and followers (Ligotti, T.E.D. Klein).

Nekronomikon had three editions so far, each slightly different in content and design, and sold in almost 4.000 copies. His other collections are also in high demand. Serbs have embraced the scribe from Providence and his cult in this country is now quite strong. From a virtual unknown, thirty years ago, he grew into a cult figure in the 21st century’s first decade, while now his name on the covers guarantees sales comparable to those of better known genre bestsellers. A nice feat for a spirit who, for more than fifty years after departing the body, evaded this part of the world. Once he was finally summoned to Serbia, he was not received as a foreigner and outsider, but as a long-lost prophet of doom whose bleak vision became immediately understandable and relevant.